Medical illustrator puts a soft edge on the hard sciences

|

| Drawing of a human figure. © 1992 Jennifer E. Fairman |

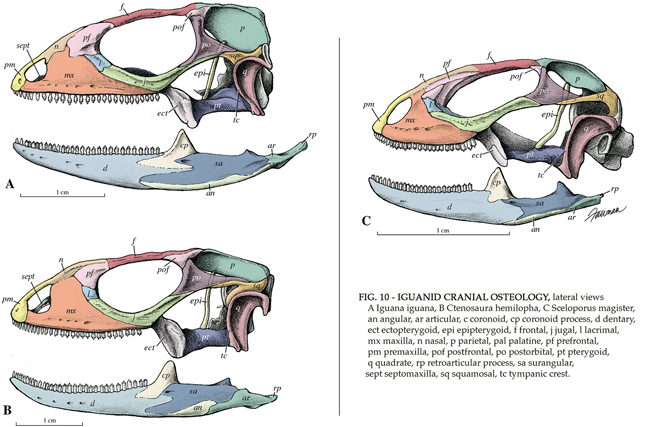

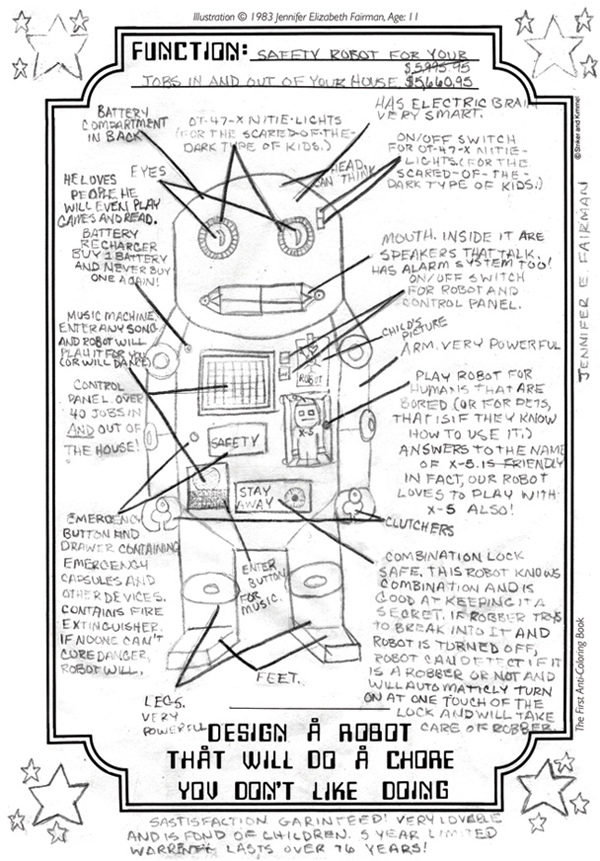

of the journal Â鶹´«Ã½É«ÇéƬ & Cellular Proteomics in December focused on post-translational modifications. To convey the complexity of the molecular biology and biochemistry involved in these modifications, was recruited to help with the illustrations and schematics as well as to design the cover art of the special issue.

Fairman is a certified medical illustrator who holds a faculty position as an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine’s Department of Art as Applied to Medicine. At Hopkins, she teaches in the department’s graduate program and does work for other Hopkins medical and science departments. She also runs her own freelance business, .

|

| Quail chick. Drawing for the Virginia Living Museum newsletter. © 1991 Jennifer E. Fairman |

|

| Safety robot. As a child, Fairman loved to draw imaginary creations in her coloring books. © 1983 Jennifer E. Fairman |

As a child

While growing up in Houston, Fairman was fascinated by her teachers. She thought it was amazing “how much teachers knew and how they shared knowledge and contributed to other people’s budding futures,” she says. She hoped to grow up to be a teacher.Fairman excelled at math and science and attended the Michael E. DeBakey High School for Health Professions. Attending a magnet school like DeBakey opened up the alternate professional career of medicine. But “in the background, there was always art. Art was my hobby, my stress relief,” she says.

When Fairman was 15, her parents relocated the family to Newport News, Va. “I was born and raised in Houston. It was all I knew at that time, so (the move) was the most devastating thing to ever happen to a kid like me!” she says with a laugh. She attended a regular high school in Newport News, but the guidance counselor knew of her passion for science and math.

One day, the nurses of Riverside Hospital came to speak to students about careers in nursing. “I was invited to go to the library to listen to them. I wasn’t really interested in nursing, but I went anyway because I could get out of German class,” says Fairman. At the library, Fairman sat at the back and began flipping through a booklet the nurses had handed out on health science careers. In flipping through the pages, a picture caught her eye.

“There was this picture of a woman sitting at a drawing table with a skull, a huge picture of an eye and some anatomical drawings around her, and all these different references. She was drawing. I thought, ‘There’s an artist! What is this?’ I wasn’t even reading what it was. I was just looking at the picture. I was so mesmerized,” recalls Fairman. “Then I looked at the title of the career, and it said ‘Medical Illustrator.’”

|

| Depiction of a 17-year cicada (Magicicada septendecim). © 1997 Jennifer E. Fairman |

Becoming a medical illustrator

Fairman had never heard of medical illustration. After school, she ran to the public library to look up the profession and found a few books, including one about Max Brödel, who had established the Hopkins department at which Fairman is now a faculty member. She became hooked: Medical illustration was going to allow her to combine her love for science with art.“I didn’t know how to become a medical illustrator. I just knew it existed,” says Fairman. Her father did the next step for her. He scouted around for programs that offered medical illustration and discovered that Hopkins offered it as a graduate program. He sent away for the undergraduate application, thinking if Fairman did her undergraduate studies there, she would have an easier time getting into the graduate program.

On receiving the undergraduate application form, Fairman promptly threw it away. She didn’t think she could get in, and “knowing how small and competitive the field was, I wanted to keep my options open,” she says.

Fairman ended up at the University of Maryland, where she pursued a dual degree in premed biological sciences and studio art. “I couldn’t decide which one to do, so I majored in both!” she says.

After she graduated, Fairman worked at the Systematic Entomology Laboratory at the National Museum of Natural History, which is part of the Smithsonian Institution. After the two-year stint, Fairman enrolled in the Hopkins graduate program.

|

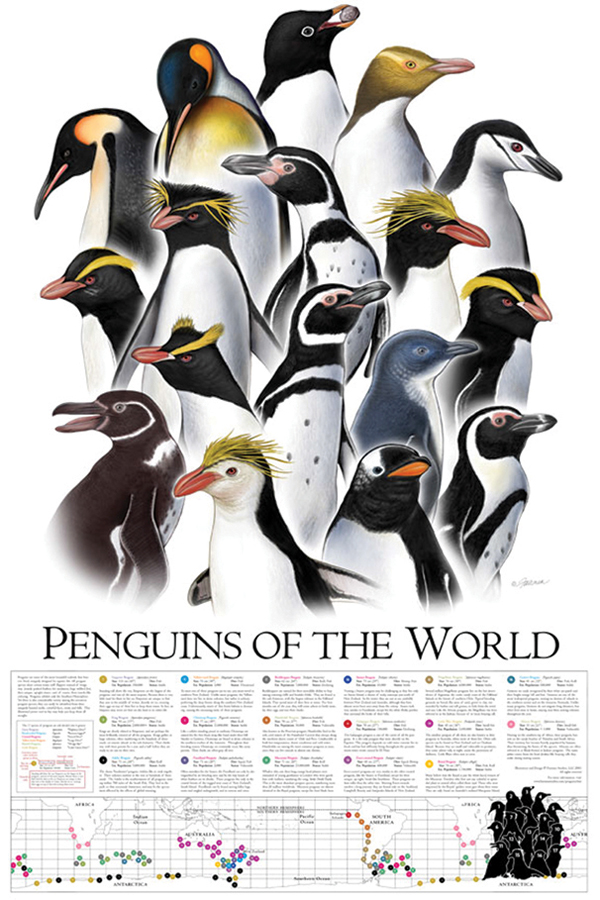

| Penguins of the World poster. The penguin portraits reproduced in this poster originally were illustrated as full-habitus images for a permanent exhibit at the Saint Louis Zoo. © 2003 Fairman Studios, LLC |

Having a good parachute

After graduation, Fairman moved to Boston to take her first position as a professional medical illustrator at the Lahey Clinic. But 14 months later, the dot-com bubble busted and budget cuts were slated. Lahey’s art department was eliminated. “I was stuck in a new city with a new career and no job. I almost moved back home. But then I decided to wing it,” she says. “As a medical illustrator, if you’re going to be pushed out of an airplane with a good parachute, Boston is a good place to land in because of its medicine and science. There’s a lot going on. It was good to be stuck in a place like that to try my hand at freelancing.” That’s how Fairman Studios got started in 1999.Fairman became certified and freelanced full time for six years, doing illustrations for patient-education materials, surgical procedures, and medical-device and biotechnology companies. During that time, she got married. But then Hopkins made Fairman an offer to return as a faculty member, so she moved her family to Baltimore. “I always wanted to be a teacher. It came full circle for me to be doing all three of the things that I love: science, art and teaching,” she says. “It’s really amazing how it all worked out.”

Fairman Studios is still running, but because her position at Hopkins is full time, Fairman has limited the time she devotes to freelancing.

|

| Systems of pneumococcal infection. The purpose of this illustration was to represent the anatomical systems of the body attacked by S. Pneumoniae, a bacterium that causes various diseases and infections, especially in young children of developing countries. © 2006 Johns Hopkins University |

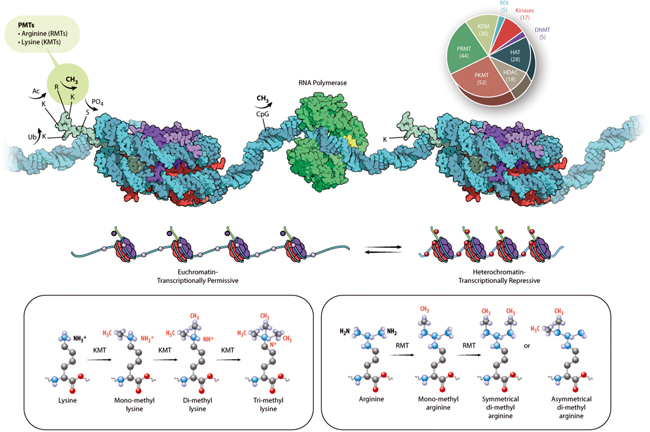

Life at Hopkins

At Hopkins, Fairman has two primary responsibilities – teaching and producing medical illustrations and animations for other Hopkins departments. She also is involved in administration of the graduate program and sits on the admissions committee.“The one thing that has stayed constant, and what probably drives and fuels me in this field, is that it’s a never-ending education,” she says. “There is always a new technique, a new piece of software or a new scientific discovery that I need to learn about. It’s very hands-on. For every project that I participate in, I become more knowledgeable, better at what I do and more precise.”

When she meets prospective students for the graduate program, she can identify those who haven’t properly researched the field. “They believe that medical illustrators sit at a drawing table all day long and draw pictures with a pencil, which are mostly anatomical,” she says. “It’s not Leonardo da Vinci every day. There are a lot of microscopic things that are being illustrated, where everything is molecular and cellular. I’m seeing that subject matter increase more. Things have become more and more focused and detailed.”

Fairman’s tools, besides the occasional pencil and paper, are Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop. For animations and interactive work, she uses Adobe After Effects and Cinema 4D and programs with HTML5. Keeping up with visualization technology is “like a marathon,” says Fairman. “If there’s one thing I find the most challenging about my job, it is keeping up with the pace of technology, because it’s rapidly changing.”

She says she is privileged to be at an institution like Hopkins, where she can easily keep up with the pace of biomedical research. “There’s a little coffee place which is the Hopkins watering hole,” she says. “There are always posters outside.” Fairman uses her daily coffee break to peruse those posters and look for seminars that might be important for her to attend. Also, “I learn so much from the assignments that I’m given by reading all the different articles about surgical procedures, molecular mechanisms, actions of drugs,” she says. “In addition to being an active member of the Association of Medical Illustrators, that’s primarily how I keep up with everything.”

Creating cover art and illustrations for MCP

The way Fairman worked on the art for the was typical for any project she does. She met with of Johns Hopkins University, the MCP associate editor overseeing the issue, and ASBMB’s publications director, Nancy Rodnan, whose idea it was to hire a professional medical illustrator. Hart explained the science in the various articles. With input from Mary Chang, MCP’s managing editor, the group focused on the images that were either schematics or illustrations. They left alone the images that were captured by a camera or a computer.“One of the things that I strived to do for this journal was to come up with a consistent style,” explains Fairman. For elements that came up repeatedly, such as ubiquitination, acetylation, proteins and organelles, Fairman established a style so that all of the figures throughout the special issue had the same look and feel. Fairman also says she stuck to scientific conventions as much as possible in terms of colors and symbols. “For example, thinking back to my time in organic chemistry in undergrad, in the little molecular model set, oxygen is usually red, carbon is black, and hydrogen is white,” she says. “Whenever we create any visual, we have to keep in mind who the audience is. Because MCP has a scientific audience, I’ve tried to come up with conventions that people are used to seeing.”

Fairman says it can be a challenge to figure out what should be kept in and left out of an illustration. She had a difficult case with one of the figures from the MCP special issue. “The illustration shows a really complicated mechanism, where these different proteins on the cell membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus, all the different organelles, are interacting with each other,” she says. “Instead of showing every single protein in its correct configuration, the best thing to do to drive home the message is to use color coding. Not worry so much about what those proteins actually look like but focus more on what they do.”

With the cover, Fairman took another tack, because the cover has a different role than figures in the scientific articles. The inspiration for the cover art came from figure 1 by Corina Antal and at the University of California, San Diego, on the dynamics of lipid second messenger phosphorylation. “The cover isn’t necessarily meant to show the whole mechanism in a way that the readers will completely understand it,” says Fairman. “It is supposed to engage them and bring them into the journal, wanting to read that featured article.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

Women’s History Month: Educating and inspiring generations

Through early classroom experiences, undergraduate education and advanced research training, women leaders are shaping a more inclusive and supportive scientific community.

ASBMB honors Lawrence Tabak with public service award

He will deliver prerecorded remarks at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting in Chicago.

ASBMB names 2025 JBC/Tabor Award winners

The six awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2024 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Daniel N. Hebert (1962–2024)

Daniel Hebert’s colleagues remember the passionate glycobiologistscientist, caring mentor and kind friend.