Budding artist

is an installation artist who has been devoted to painting and drawing since she was a teenager. While working toward a Ph.D. in art, an exercise in using computer algorithms to bring still pictures to life led to a revelation. The natural world must have its own algorithms, Kudla thought, parallel “operating systems” that animate life.

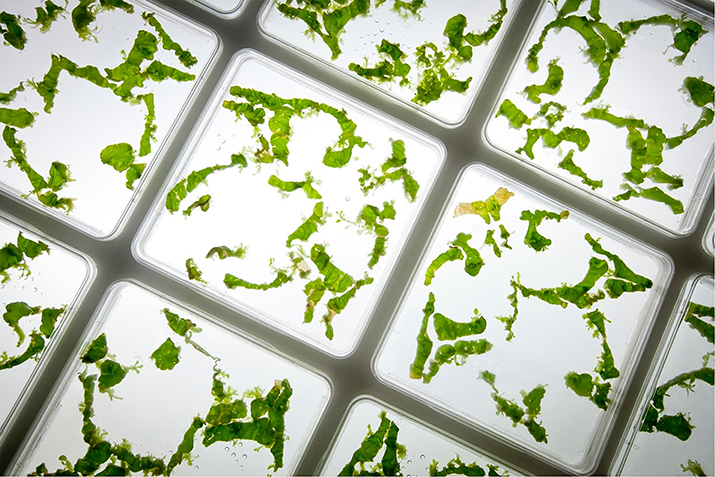

Trimmed leaves under tiles give off new tissue in “Growth Pattern”

Trimmed leaves under tiles give off new tissue in “Growth Pattern” Kudla's art melds natural and artificial processes. ALL PHOTOS COURTESY OF ALLISON KUDLA

Kudla's art melds natural and artificial processes. ALL PHOTOS COURTESY OF ALLISON KUDLA

Hooked on exploring this concept, Kudla began pursuing projects that create an interplay between natural systems, scientific techniques and futuristic technology. Now it’s her calling card. She makes art that blurs the barriers between what’s natural and what’s artificial.

Blurring barriers

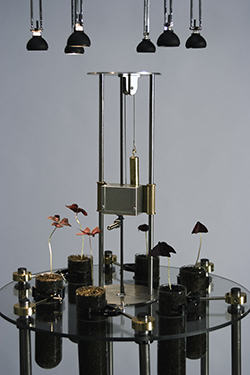

One of Kudla’s early projects exploits phototropism, the ability of a plant to orient itself toward or away from a source of light. In “The Search for Luminosity” Kudla employs a collection of phototropic plants to surround a machine containing a light source and a sensor. On first glance, the plants seem to open and close their leaves in relation to available light — the leaves flap open when the light source hovers above them. But Kudla has in fact manipulated each plant in the installation to expect the source at a certain time. When its leaves start to move in anticipation of the light, the machine’s sensor notes the movement and sends the source over to bathe the plant in light. Kudla has, in effect, reoriented the sequence that would occur naturally between a plant and the sun by programming the light to intensify in relation to the plant’s movements, instead of the other way around.

Wet labs in art school

Kudla describes a conference that she attended recently to which artists and designers had been invited for the first time. “I met a lot of artists who were working on setting up wet labs in their art schools, and I also met scientists who are interested in seeing the creative thinking that artists can bring to problems. With the addition of arts, suddenly things became more focused on what we’re doing — larger questions about how human culture is evolving and what we want to do in this world, as opposed to how to incrementally move forward a specific technology.”

Kudla earned her doctorate from an innovative program known as at the University of Washington. During her time at UW, she had many resources at her disposal, including access to lab equipment and a diverse array of scientists, which allowed her to experiment and flourish.

“I didn’t have a very validating relationship with science and math when I was younger, and it took approaching those disciplines from an artistic perspective for me to figure out how to find some passion or motivation within those fields,” she says.

The arts and sciences both rely on curiosity for invention, and Kudla feels that a strict allegiance to either field is less important than this shared sense of curiosity. “I think that what should be cultivated is curiosity and the ability to find interest in things and pursue them wherever they lead, from whatever perspective the individual has.”

Living systems on display

Kudla’s creative unpacking of living systems is on display in her best-known work, “Capacity.” For this work, she uses a 3-D printer to create a living fractal with a pattern that mimics both an aerial view of the growth of cities and a microscopic look at the growth of cells. The printer deposits algae and seeds that are contained in a clear gel growth medium into a sealed case. As time passes, the deposited life sprouts, and what should be a still, printed object becomes a living, changing form.

For “Growth Pattern,” a more recent work, Kudla uses hormones to stimulate plant leaves to give off new growth, taking advantage of their totipotency. Totipotency is the ability of a plant cell to differentiate into any kind of cell that’s needed for the plant’s growth. These leaf cells are treated with hormones that allow them to give off new leaf tissue.

First cut into abstract representations of flora, the leaves in “Growth Pattern” are then suspended in square tiles containing water and nutrients. Over time, some of these sterilized tiles are invaded by fungus and bacteria. This process of growth and decay remains on display and is tracked photographically over the course of several weeks.

Oxalis plants interact with light in “The Search for Luminosity”

Oxalis plants interact with light in “The Search for Luminosity”

Working the system

Because all of Kudla’s work incorporates live materials, it is impermanent and must be continually set up and broken down. While this quality makes her work unique, it also makes it difficult to support herself through sales. Until recently, Kudla relied on residencies to keep herself afloat.

She recently moved to the , a nonprofit organization for experimental life sciences research, where she works in their visual design department. The ISB focuses on the idea of consilience — as Kudla puts it, “the merging of disciplines to solve complex problems” — which makes it an appropriate place for someone with her background.

“Systems biology values the integration of biological systems across all scales, from the molecular and cellular to the organism and its environment,” she says. “There is an important need to look at those scales and not become fixated on any one aspect of that multiscale system, but look at the interactions in that system.”

Kudla is committed to giving artistic perspectives on science a more prominent place at the ISB. She also advocates for alternative modes of education that allow for a more hands-on and creative introduction to science early on.

Kudla believes the arts and sciences have much to learn from one another. “In art, the language of praise for what makes an artwork successful is less clear than it is in science, which allows art to explore realms that could potentially be, not necessarily more innovative, but more creative,” she says.

She hopes that her work both will inspire others to follow in her footsteps and will help create more opportunities for people who are talented at merging disciplines.

“If the humanities and technical fields were not so obviously separated,” she says, “then perhaps somebody who has a more humanistic perspective on things would learn math or science from their unique perspective and create something entirely unexpected.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and weโll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

ASBMB names 2025 fellows

ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ and ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ Biology honors 24 members for their service to the society and accomplishments in research, education, mentorship, diversity and inclusion and advocacy.

When Batman meets Poison Ivy

Jessica Desamero had learned to love science communication by the time she was challenged to explain the role of DNA secondary structure in halting cancer cell growth to an 8th-grade level audience.

The monopoly defined: Who holds the power of science communication?

โAt the official competition, out of 12 presenters, only two were from R2 institutions, and the other 10 were from R1 institutions. And just two had distinguishable non-American accents.โ

In memoriam: Donald A. Bryant

He was a professor emeritus at Penn State University who discovered how cyanobacteria adapt to far-red light and was a member of the ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ and ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ Biology for over 35 years.

โฏYes, I have an accent โ just like you

When the author, a native Polish speaker, presented her science as a grad student, she had to wrap her tongue around the English term โfluorescence cross-correlation microscopy.โ

Professorships for Booker; scholarship for Entzminger

Squire Booker has been appointed to two honorary professorships at Penn State University. Inayah Entzminger received a a BestColleges scholarship to support their sixth year in the biochemistry Ph.D. program at CUNY.