The taxi driver's book

Very early on a dark and cold January morning in Scotland, Stanford University’s climbs into the back of a taxi, ready to head home to the U.S. Still half asleep, she settles into her seat for the hourlong drive from the to Edinburgh airport. A few minutes into the ride, which winds through stone villages, past patterned green hillsides and over bridges that cross the River Tay, her cabbie — who also drove her to the university when she arrived in Dundee — makes a surprising request. He asks Pfeffer, an expert in the study of receptors in human cells, if she’d like to see his guestbook.

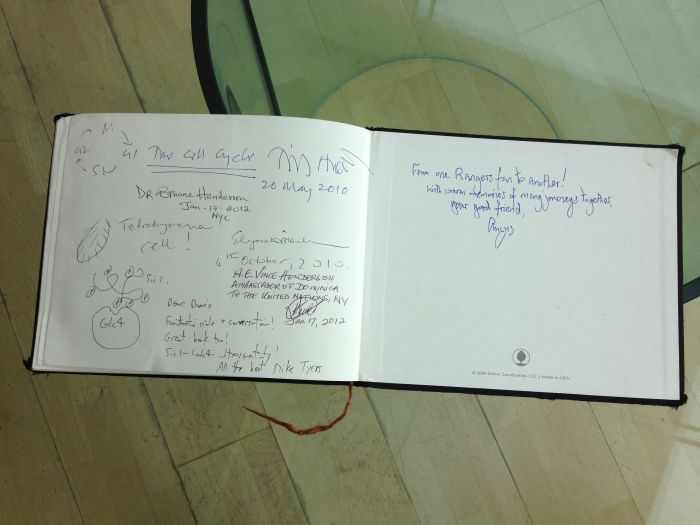

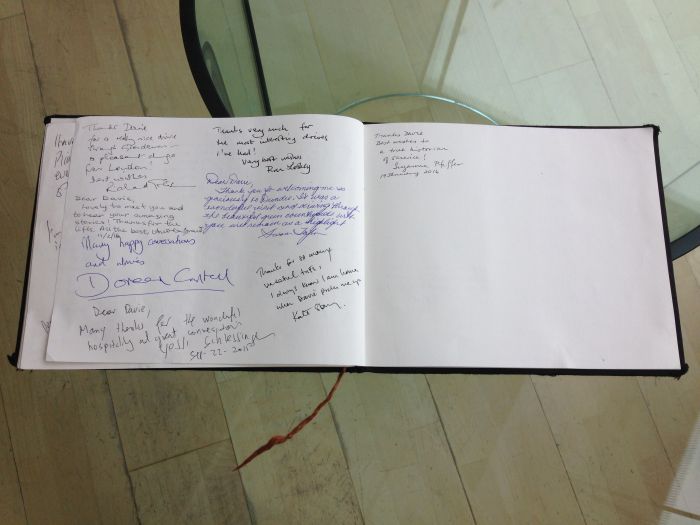

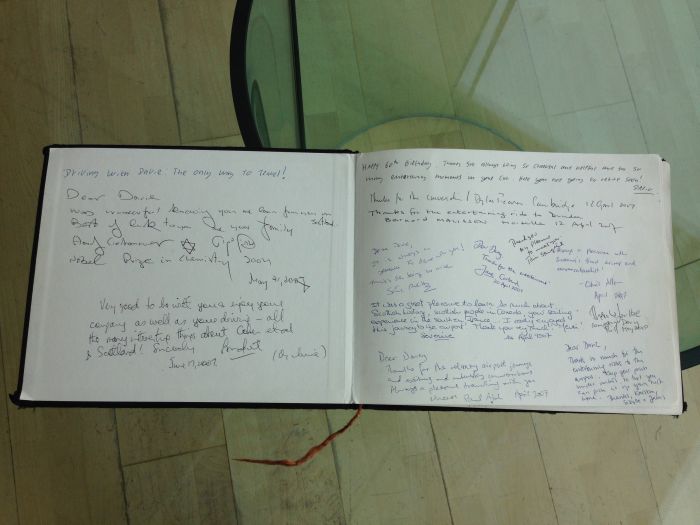

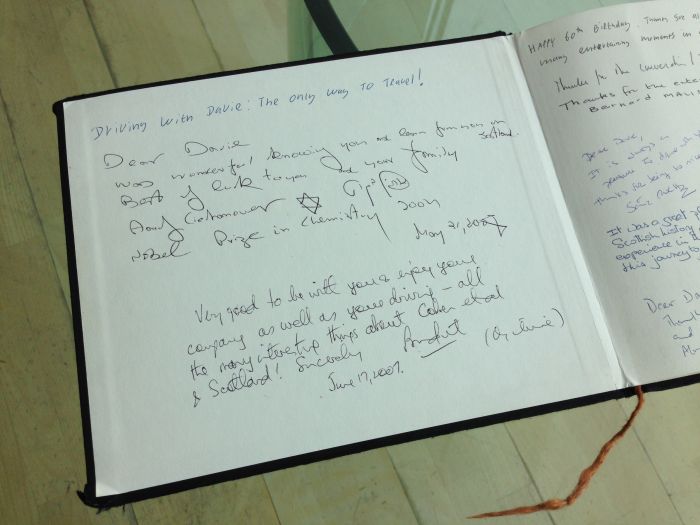

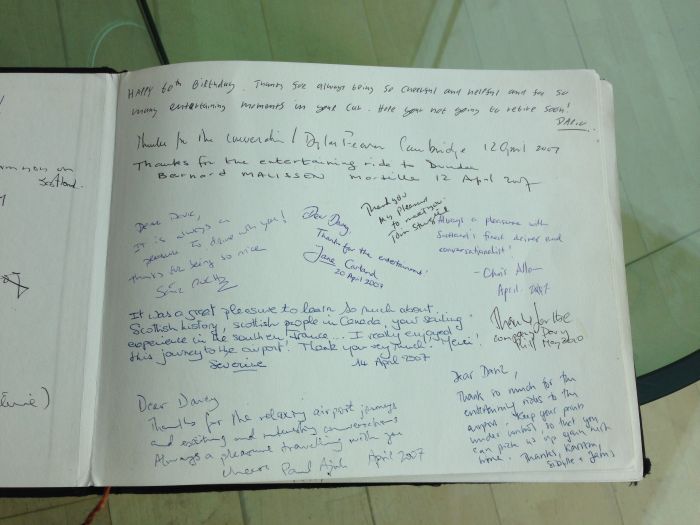

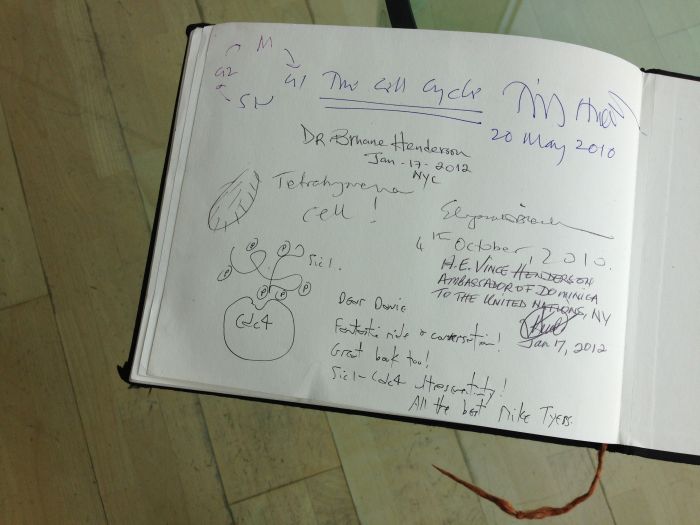

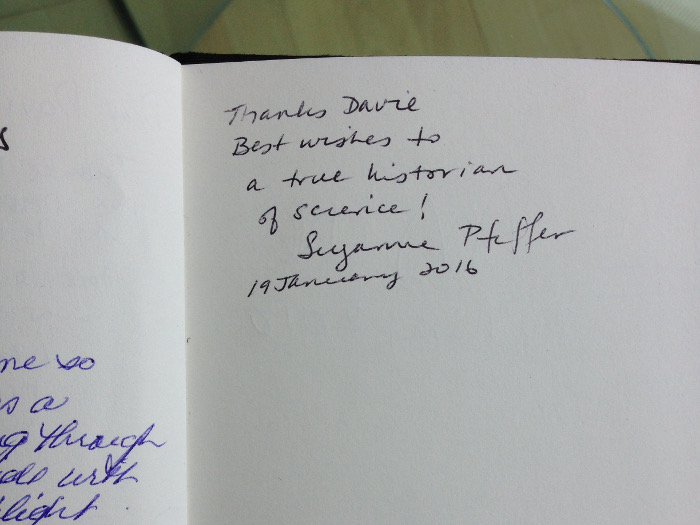

Pfeffer agrees, and the driver hands her a book with a simple, dark blue cover that is tattered at the edges from years of use. As she leafs through, she sees a hodgepodge of scribbled sentiments, sketches and signatures. When she looks more closely, Pfeffer realizes the signatures comprise a veritable who’s who of the life sciences. Among the scrawls of notable scientific contemporaries, Pfeffer can make out the names of four Nobel laureates. There’s , who drew an off-kilter sketch of a cell cycle alongside his note. And there are , and .

Soon Pfeffer, who is a former president of the ֲי¶¹´«ֳ½ֹ«ַיֶ¬ and ֲי¶¹´«ֳ½ֹ«ַיֶ¬ Biology, is deep in conversation with her cabbie and struck by the depth of his knowledge about his former passengers.

Remembering their interaction some months later, she says, “He really understood how important these riders were, and in what esteem we, as scientists, hold them.”

Soliciting signatures

For the past 20 years, 69-year-old Davie Douglas has worked as the driver for the at the University of Dundee. A hub for local and international research into cell signaling and other biological processes, the university attracts a plethora of scientists to its facilities. (Nearby golf courses and whisky distilleries are also part of the draw.) For the past nine years, Douglas has been collecting the signatures of these scientists in his guestbook.

Douglas acknowledges that some of his scientist passengers are true luminaries but is pragmatic about his interactions with them. “They’re just normal people, like ourselves,” he says. “They just get in your car and talk away.”

It’s rare, Douglas says, for his riders to talk about science, and his intuition tells him it’s best not to push. “I think they’re usually fed up by talking science. They’d rather just talk about football or anything else that comes to their minds.”

Douglas’ guest book was born of a conversation he had with , director of the Medical Research Council Protein Phosphorylation and Ubiquitylation Unit at the university. Knowing how many prominent scientists were using Douglas’ services, Alessi suggested a book as a means of preserving those interactions. Douglas was hesitant and put off buying the book. But Alessi persisted.

“Dario says, ‘Did you get a book yet?’ I say, ‘No.’ He says, ‘Here you are. There’s a book here for you.’”

With the guestbook thrust upon him, Douglas began requesting signatures from his passengers. But not everyone was asked to sign. Joking, Douglas says, “You can’t just sign the book. You’ve got to be invited to sign the book! If I didn’t like ya, ya didn’t get to sign the book.”

He clarifies that scientists not being asked to sign is only ever a result of his own forgetfulness.

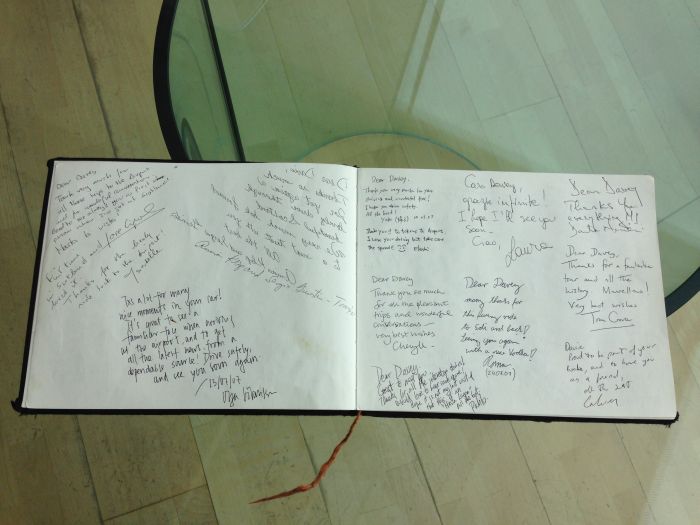

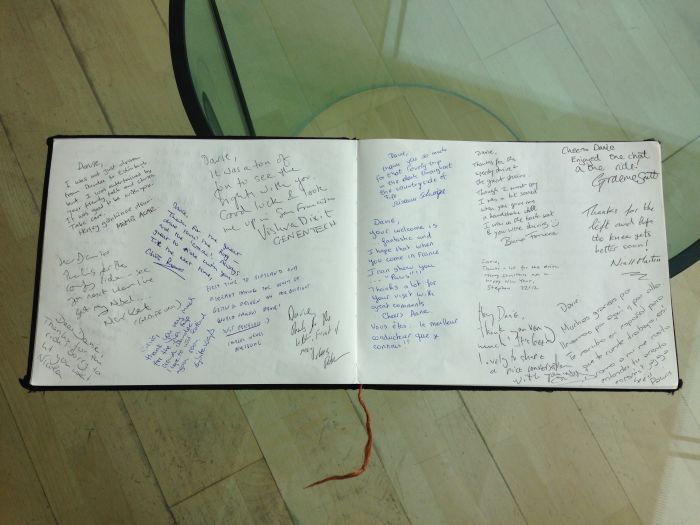

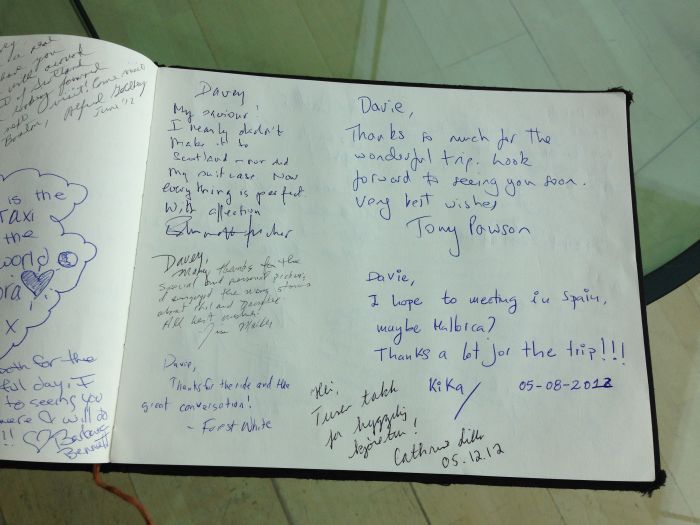

A treasure trove of notes from biochemistry greats, the book now contains more than 450 signatures, filling 33 pages. As Alessi says, Douglas “probably meets more eminent scientists than the average scientist would meet in their working career.”

The guestbook showcases a whimsical side of some of these revered scientists. A playfully drawn tetrahymena cell sits alongside Elizabeth Blackburn’s message. It’s just above a sketched interaction between two cell-cycle proteins from another signee, systems biologist . The whole book reads more like a yearbook, with doodles, meaningful thank-you’s and promises to come back soon filling the pages.

Prelude to a cabbie

Davie Douglas wasn’t always a cab driver. He started out as a seaman, a member of the British Merchant Navy. While in port in Dundee doing some shore-based work, he started taking fares on the side.

“I really hated it. I was getting ready to go back to sea,” Douglas says. Then one fateful morning, his daughter called.

It was early. Douglas was still in bed. His daughter, who was a graduate student at the University of Dundee at the time, told him the school’s taxi driver had failed to show up. Douglas agreed to take the university’s waiting guests to the airport.

That early-morning drive set his new career in motion. Before he knew what was happening, the university was helping him get a cell phone to make contacting him for jobs easier. A self-proclaimed technophobe, it took a while for Douglas to become accustomed to this new work. “The first mobile phone I ever had was the size of a brick,” Douglas says with a laugh. “I still am really computer illiterate, and I’m quite happy to stay that way.”

But Douglas manages well enough. His job now revolves around that cell phone, which he uses to coordinate transportation for staff and visitors to the School of Life Sciences.

Preserving a family record

Pfeffer says it was “priceless” to page through the book as they were driving through the Scottish countryside and see so many recognizable names together in one place. “I knew all the people,” she says. “They were all part of the family of science.”

Those who know Douglas say that his charm and goodwill make creating this kind of family record possible. He is known for going above and beyond to entertain his passengers. According to Alessi, “If someone’s got a bit more time to get to the airport he’ll take them on the more scenic route and show them around Scotland.”

In caring for his passengers, the line between job and lifestyle often blur. “I don’t even consider myself a taxi driver anymore,” Douglas says. “I’ve got a meter in my car, and I couldn’t even tell you how to turn it on.” But he wouldn’t have it any other way. He has, he says, “the best job in the world.”

Alessi says that Douglas also helps keep his University of Dundee family on track. “Often if you want to find out what’s going on in the university the quickest way is just to have a 10-minute conversation with Davie, who can bring you up to speed.”

The book is now almost full. Douglas would like to get the pages laminated and make it available for others to read. With his 70th birthday looming, Douglas also hopes to wrap up his taxi career within the year. But for now, he continues to do the work that he loves. It’s work that Pfeffer thinks could have a lasting impact. As she says, he’s recorded a history of science “simply by having a guest book in his car.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and weג€™ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

What seems dead may not be dead

Vincent Tagliabracci will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientist Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12ג€“15 in Chicago.

'You can't afford to be 15 years behind the parasite'

David Fidock will receive the Alice and C.C. Wang Award in ֲי¶¹´«ֳ½ֹ«ַיֶ¬ Parasitology at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12ג€“15 in Chicago.

Elucidating how chemotherapy induces neurotoxicity

Andre Nussenzweig will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12ג€“15 in Chicago.

ASBMB committees welcome new members

Committee members serve terms of two to five years, and a number of new members have joined. We also thank those whose terms have ended.

Curiosity turned a dietitian into a lipid scientist

Judy Storch will receive the Avanti Award in Lipids at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12ג€“15 in Chicago.

From receptor research to cancer drug development: The impact of RTKs

Joseph Schlessinger will receive the ASBMB Herbert Tabor Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12ג€“15 in Chicago.