Q&A with Jeremy Berg

Jeremy Berg has kicked off his tenure as the 83rd president of the ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ and ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ Biology. Berg’s career has straddled academia and government. He began his independent research career in the department of chemistry at Johns Hopkins University working on zinc-finger proteins. At the age of 32, he was appointed director of the department of biophysics and biophysical chemistry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, making him one of youngest department chairs in the university’s history. In 2003, Elias Zerhouni, then the director of the National Institutes of Health, tapped Berg to head the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which he did for eight years. Berg has been at the University of Pittsburgh for a year now, a move he famously made as the “trailing spouse” to support his wife’s career. He is the university’s associate senior vice-chancellor of science strategy and planning and holds a faculty position in the department of computational and systems biology. Berg spoke with ASBMB Today about his current research interests; the influence of his wife, radiologist Wendie Berg, on his work; and his view of the current scientific landscape. Below are excerpts from the interview, edited for length and clarity.

|

| Jeremy Berg at Glacier National Park in the summer of 2010. Photo courtesy of Berg. |

Your research at the University of Pittsburgh is focused on peroxisomes. How did you get interested in them?

Berg: It’s a project my lab (at Hopkins) started over a decade ago. It was brought to my lab by an M.D./Ph.D. student who had done a rotation in a cell biology lab that was working on peroxisomes. He was interested in trying to understand the structural basis for targeting signal recognition. The molecules that were involved in the process had been identified, and the question was, “What’s the structural basis for the recognition?” We solved the structure of the complex between the receptor protein and the targeting peptide over 10 years ago and have been working on it pretty much ever since. At Pitt, I’m mostly focused on using computational methods to understand a lot of the data that we’ve accumulated over the years. We’re working on why particular peptides bind more tightly than others and testing state-of-the-art methods for calculating binding affinities from structures.

What have you found so far?

Berg: We have looked at all the proteins in the human proteome that have the most common type of targeting signal. There are approximately 50 different proteins. We found the affinities ranged over almost four orders of magnitude. We discovered there was a very suggestive correlation between the affinity of targeting signal and the abundance of the mRNA. The more abundant proteins have lower-affinity targeting signals, and less abundant proteins have higher-affinity targeting signals. It makes sense from a chemical and biochemical point of view.

How do you see the landscape of biochemistry and molecular biology now?

Berg: It’s now possible, both technically and intellectually, to think not just about one protein and one ligand at a time but to think about a whole system. We can really understand how the pieces compete with each other and fit together. We can connect the individual molecular interactions with biochemistry and physiology.

How would you say science has evolved over the course of your career?

Berg: When I was first starting out, there were completely unknown classes of proteins that are now well characterized and contain large numbers. I started off my independent career working on zinc-finger proteins after the first of those proteins was discovered in frogs. Within the first year or so, it became clear that there were members of the same family in other organisms, such as Drosophila, yeast and humans. Within a few years, it was clear it was one of the largest, if not the largest, families of proteins in many eukaryotic organisms. Those sorts of trends have occurred across many different fields.

Another big change is it used to be that biochemistry was much more of a data-gathering problem. These days, with a lot of new technology, data gathering is much more straightforward. People are generating vastly more data than they have time or ability to analyze. That’s one of the reasons why I ended up going to a department of computational and systems biology. There are so many data out there waiting for new tools to be analyzed.

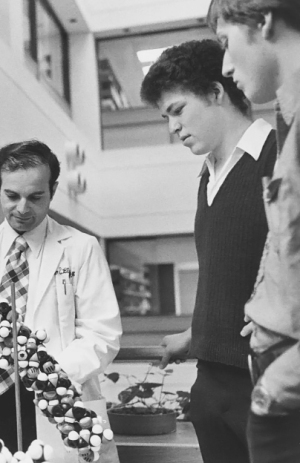

|

| Jeremy Berg, center, as a college freshman at Stanford University in the laboratory of Lubert Stryer, left, in 1977. At right is Alex Wlodawer, then a postdoctoral fellow working with Keith Hodgson. Wlodawer is now a laboratory chief at the National Cancer Institute. Photo courtesy of Berg. |

What would you say were the turning points in your career and life?

Berg: On the professional front, I decided after I finished my Ph.D. to do my postdoctoral training in something very different. I changed fields almost completely, away from pure chemistry and into biochemistry. At that point, it just was an exploration, but it turned out to be an irreversible change. That has had a huge impact on what I’ve ended up doing throughout my career. I also decided, after much thought, to take an opportunity to become a department chair at a time when it was pretty scary to be taking on extra responsibilities. But it turned out to be something that I really enjoyed and was good at. Once I got into administration, I got a taste for it and took advantage of opportunities to get involved in bigger issues. I’ve enjoyed that.

On the personal side, my postdoc coincided with getting back together with my old college girlfriend, who has been my wife for almost 28 years now. She’s an M.D./Ph.D. In addition to our lives and family together, she has a big influence on the breadth of my scientific and medical knowledge. She does patient care and clinical research. Because of that, we have frequent conversations about research and how to make a difference in the lives of people.

What’s the one piece of advice you wish you had been given when you were younger?

Berg: Don’t be afraid to explore ideas that are pretty far away from your comfort zone. It’s something that I ended up doing but in a much more haphazard method than driven by advice.

You and your wife have successful careers as well as three children. How do you balance the demands of work and family?

Berg: It’s been a combination of things. When we first married, we decided that we would have kids and then build our lives around them. When you have children to deal with, you can’t worry and plan. You just go through (each day). The other thing was we were lucky that Wendie’s mother had just retired when our first son was born. She came out to help for the first few weeks after he was born and ended up staying with us for about 13 years, although this arrangement was not without its tensions. She’s now 92 and just moved with us to Pittsburgh from Maryland so that we can help take care of her. She’s been part of our (household) more than 25 years now.

There are certainly compromises when you have young children and a wife with clinical responsibilities where there isn’t much flexibility. I didn’t spend as much time in the lab as I probably would have otherwise. The upside of that was I spent more time thinking rather than doing. I think there’s a big lesson in that. Rather than doing the next experiment, it’s better to take some time and really digest what you’re doing, think about strategy and how to approach the problem, instead of just charging ahead enthusiastically without doing the same amount of thinking.

What’s your advice to postdocs and graduate students?

Berg: There’s a myth that most postdocs and graduate students go into academic careers. The reality is that they go off and do lots of other different things. Some go into academia. Some go into biotechnology or pharmaceutical companies, policy or writing. Certainly, my own students and postdocs have done a wide range of things. I think it’s a good thing for all concerned.

The question is how to prepare yourself. I think it’s fairly simple. The skills that you need are critical thinking, writing, expressing yourself and organizing your time. Those skills help you in academia or whatever you do. Be broadminded about what the options might be, do a fair bit of self-examination, and think through your priorities and what you want. That way, you are prepared to make decisions about how to pursue your career when an opportunity or challenge presents itself.

|

| Jeremy Berg at a 2010 Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology-sponsored briefing about the importance of basic science for congressional staff on Capitol Hill. Photo courtesy of Berg. |

How would you like to reach out to the community as ASBMB president?

Berg: I want to make it clear to the members of the society that I want to hear from them. I want to make sure I and other leaders of the society are aware of their issues and perspectives. I am sure there will be more structured opportunities for collecting that input as I go forward as president.

From my experience at NIGMS, it made my job as an institute director much easier when I had a better sense of the real concerns and priorities of the community rather than trying to guess them. It was also bidirectional. By allowing people to know what was going on at NIH, the conversations were richer and more substantial because they had the same background facts about what was happening. I hope to achieve the same sort of thing at ASBMB.

What are your hobbies?

Berg: Certainly, work and family keep us pretty busy! I was always a bit of a news junkie, and that got worse when I was at the NIH and closer to the government. I do a fair bit of reading of news and analysis. I have a new home in Pittsburgh, so I am working on getting fully unpacked and the garden under control. I used to love to make molecular models and jewelry, particularly with Indian beads. Hopefully I will have time to get back to that before not too long. It’s become much more challenging with aging eyes than when I was a teenager and could see everything!

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and weโll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

ASBMB names 2025 fellows

ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ and ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ Biology honors 24 members for their service to the society and accomplishments in research, education, mentorship, diversity and inclusion and advocacy.

When Batman meets Poison Ivy

Jessica Desamero had learned to love science communication by the time she was challenged to explain the role of DNA secondary structure in halting cancer cell growth to an 8th-grade level audience.

The monopoly defined: Who holds the power of science communication?

โAt the official competition, out of 12 presenters, only two were from R2 institutions, and the other 10 were from R1 institutions. And just two had distinguishable non-American accents.โ

In memoriam: Donald A. Bryant

He was a professor emeritus at Penn State University who discovered how cyanobacteria adapt to far-red light and was a member of the ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ and ย้ถนดซรฝษซว้ฦฌ Biology for over 35 years.

โฏYes, I have an accent โ just like you

When the author, a native Polish speaker, presented her science as a grad student, she had to wrap her tongue around the English term โfluorescence cross-correlation microscopy.โ

Professorships for Booker; scholarship for Entzminger

Squire Booker has been appointed to two honorary professorships at Penn State University. Inayah Entzminger received a a BestColleges scholarship to support their sixth year in the biochemistry Ph.D. program at CUNY.