Chasing the diagnostic potential of RNA editing

wears many hats: He is a practicing physician, he is the division chief of gastroenterology at Washington University in St. Louis, and he holds professorships in medicine, developmental biology, and pharmacology and molecular biology. On top of that, he is the co-editor-in-chief of the Journal of Lipid Research and a principal investigator studying the genetic regulation of intestinal and hepatic lipid homeostasis, with .

A by Davidson and colleagues, published in RNA Journal, deepens our understanding of tissue-specific regulation of programmed alteration of RNA, known as RNA editing, in the intestine and the liver.

“This paper identifies what we believe to be the complete machinery for a form of RNA editing,” Davidson said. “The approaches and the tools from this study can be applied to gain a better understanding of the function of most, if not all, types of mammalian cells.”

Davidson’s professional journey and scientific outlook was captured in ASBMB Today in a . In brief, his interest in gastroenterology emerged during his medical training at Kings College Hospital Medical School in London under the mentorship of , one of the trailblazers of liver transplantation. He further built his expertise by working with the late at The Rockefeller University in New York and during a gastroenterology fellowship at Columbia–Presbyterian Medical Center. His own lab started at the University of Chicago Medical Center before relocating to St. Louis. His research has helped shape the field of RNA editing over several decades.

The RNA editing team in the Davidson lab at Washington University in St. Louis include, from left, Saeed Soleymanjahi, Nick Davidson and Valerie Blanc.Courtesy of Nick DavidsonRNA editing can create heterogeneity in genetically identical cells by mediating amino acid substitutions, alternative isoform creation and modification of stop codons. Furthermore, RNA editing in the 3’-untranslated region has been shown to be the alteration that most frequently leads to changes in RNA stability, RNA localization and protein translation. Advances in high-throughput sequencing techniques have shown that RNA-editing events are more pervasive than originally thought, prompting the introduction of the concept of an epitranscriptomic code to parallel the epigenetic code.

The RNA editing team in the Davidson lab at Washington University in St. Louis include, from left, Saeed Soleymanjahi, Nick Davidson and Valerie Blanc.Courtesy of Nick DavidsonRNA editing can create heterogeneity in genetically identical cells by mediating amino acid substitutions, alternative isoform creation and modification of stop codons. Furthermore, RNA editing in the 3’-untranslated region has been shown to be the alteration that most frequently leads to changes in RNA stability, RNA localization and protein translation. Advances in high-throughput sequencing techniques have shown that RNA-editing events are more pervasive than originally thought, prompting the introduction of the concept of an epitranscriptomic code to parallel the epigenetic code.

In 1994, Davidson’s team showed that one mechanism of RNA editing is the deamination of cytosine to uracil, which is catalyzed by the Apobec family, including Apobec-1. Other researchers later discovered that the Apobec-1 biochemical function requires a cofactor, and two different essential cofactors were discovered — Apobec-1 complementation factor, or A1cf, and RNA binding motif protein 47, or Rbm47.

Prior to this paper, the relative contribution of the two cofactors to physiological Apobec-1 function was not fully understood. Davidson’s team looked at the global RNA-editing landscape of mouse livers and intestines when either or both cofactors were deleted or were overexpressed as transgenes. Deletion of Rbm47, but not A1cf, caused a large, tissue-specific change in the RNA editing profile, with the intestines being most affected.

“The findings of this paper were somewhat surprising, since A1cf was discovered as necessary for the deaminase Apobec-1 to act on RNA, and it was originally thought to be the Apobec-1 cofactor,” Davidson said. “However, our data using a conditional tissue-specific deletion of Rbm47 alone or with A1cf point to Rbm47 as the dominant Apobec-1 cofactor in adult mouse liver and intestine.”

Davidson’s lab now is using the genetic tools from this study to illuminate further the role of RNA editing during development, where it is implicated in regulation of growth.

RNA-editing alterations also have been reported in cancers and neurological disorders, and Davidson’s lab is pursuing the profiling of DNA, RNA and protein levels in cancer tissues to substantiate further the diagnostic potential of RNA editing.

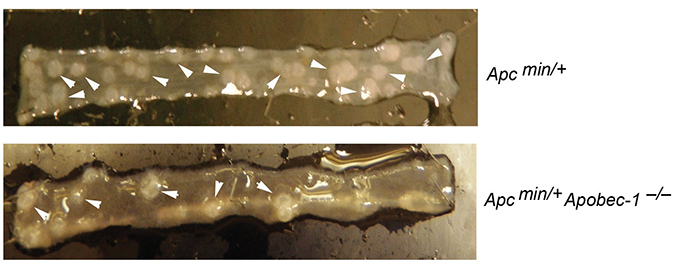

“This study fits into the emerging consensus in cancer biology that RNA editing can contribute to cancer susceptibility,” he said, “and this is a big direction that we are focusing on.” Apcmin/+ is a mouse model for tumorigenesis. The top image shows a representative section of the intestine of an Apcmin/+ mouse. Arrows denote some of the many polyps. Deletion of the RNA-editing enzyme Apobec-1 in this model drastically reduces the number of polyps in the intestine. The Davidson lab is exploring how loss of cytosine to uracil RNA editing protects against intestinal tumorigenesis.Courtesy of Nick Davidson

Apcmin/+ is a mouse model for tumorigenesis. The top image shows a representative section of the intestine of an Apcmin/+ mouse. Arrows denote some of the many polyps. Deletion of the RNA-editing enzyme Apobec-1 in this model drastically reduces the number of polyps in the intestine. The Davidson lab is exploring how loss of cytosine to uracil RNA editing protects against intestinal tumorigenesis.Courtesy of Nick Davidson

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

'You can't afford to be 15 years behind the parasite'

David Fidock will receive the Alice and C.C. Wang Award in Â鶹´«Ă˝É«ÇéƬ Parasitology at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

Elucidating how chemotherapy induces neurotoxicity

Andre Nussenzweig will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

Where do we search for the fundamental stuff of life?

Recent books by Thomas Cech and Sara Imari Walker offer two perspectives on where to look for the basic properties that define living things.

UCLA researchers engineer experimental drug for preventing heart failure after heart attacks

This new single-dose therapy blocks a protein that increases inflammation and shows promise in enhancing muscle repair in preclinical models.

The decision to eat may come down to these three neurons

The circuit that connects a hunger-signaling hormone to the jaw to stimulate chewing movements is surprisingly simple, Rockefeller University researchers have found.

Curiosity turned a dietitian into a lipid scientist

Judy Storch will receive the Avanti Award in Lipids at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.