Scientists sweep cellular neighborhoods where Zika hides out

Most people infected with Zika never show symptoms. But the virus sometimes causes severe disability — from microcephaly in babies to weakness or partial paralysis in adults — and there is no treatment. In in the journal �鶹��ýɫ��Ƭ & Cellular Proteomics, researchers report a comprehensive study of how the virus interacts with host cells. One of their findings gives insight into how Zika escapes immune signaling and proliferates inside the body.

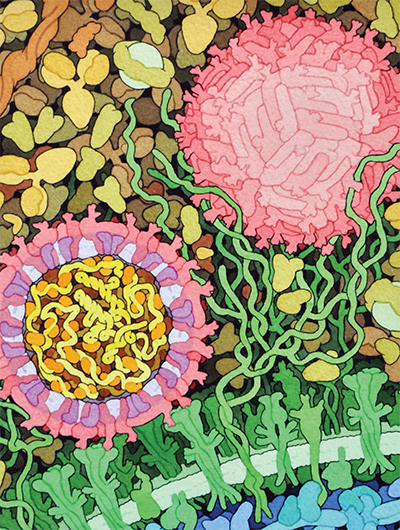

This space-fill drawing shows the outside of one Zika virus particle (red and pink) and a cross-section through another as it interacts with a cell. Courtesy of David Goodsell/Wikimedia Commons

This space-fill drawing shows the outside of one Zika virus particle (red and pink) and a cross-section through another as it interacts with a cell. Courtesy of David Goodsell/Wikimedia Commons

Like most viruses, Zika accomplishes a lot with a few tools. It has just one protein coding gene, which produces a single polypeptide that’s cleaved into 10 smaller proteins — a number dwarfed by the estimated 20,000 protein-coding genes in a human cell. Nevertheless, Zika can take over the vastly more complex human cell, repurposing it into a virus factory. , a researcher at the University of Toronto, said he found that process fascinating.

“With just these 10 proteins, this crazy virus turns your cells into zombies that do its bidding,” Raught said. “I always found that mind-blowing.”

Researchers in Raught’s lab, led by postdoctoral fellow Etienne Coyaud, wanted to find out how the handful of Zika proteins were able to hijack the host cell. They knew that the feat must depend on physical interactions between viral proteins and proteins native to the cell — but which ones?

Because of the increasing evidence linking Zika infections in expectant mothers to microcephaly in their children, Raught said, “We thought it better to leave the actual virus work to the experts.”

Instead of using infectious material, the team made 10 strains of human cells, each expressing one of Zika’s 10 proteins. By adding a small epitope tag to each viral protein, they were able to retrieve the viral proteins using an antibody that binds to this tag. The host proteins that stuck tightly to each viral protein came along for the ride; the researchers used mass spectrometry to identify those human proteins.

But there was a drawback to using this approach. What if proteins from the human cell were interacting with Zika proteins but separating from them before being extracted? To identify proteins that are close to but not inseparably intertwined with each viral protein, the team used a second technique called proximity labeling. In essence, they rigged each viral protein with an enzyme that would attach a sticky biotin tag onto anything that came close enough.

Proximity labeling is especially useful for detecting interactions with proteins embedded in cell membranes; those molecules are notoriously difficult to isolate.

“This is a really big asset of a proximity-labeling approach compared to traditional approaches,” Coyaud said.

Because Zika, like many viruses, enters the cell in a membrane-bound envelope and reorganizes many of its host’s membrane-bound organelles in the course of infection, its interactions with membrane proteins might be key to understanding the viral life cycle.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Early lipid changes drive retinal degeneration in Zellweger spectrum disorder

Lipid profiling in a rare disease mouse model reveals metabolic shifts and inflammation in the retinal pigment epithelium — offering promising biomarker leads to combat blindness.

How sugars shape Marfan syndrome

Research from the University of Georgia shows that Marfan syndrome–associated fibrillin-1 mutations disrupt O glycosylation, revealing unexpected changes that may alter the protein's function in the extracellular matrix.

What’s in a diagnosis?

When Jessica Foglio’s son Ben was first diagnosed with cerebral palsy, the label didn’t feel right. Whole exome sequencing revealed a rare disorder called Salla disease. Now Jessica is building community and driving research for answers.

Peer through a window to the future of science

Aaron Hoskins of the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Sandra Gabelli of Merck, co-chairs of the 2026 ASBMB annual meeting, to be held March 7–10, explain how this gathering will inspire new ideas and drive progress in molecular life sciences.

Glow-based assay sheds light on disease-causing mutations

University of Michigan researchers create a way to screen protein structure changes caused by mutations that may lead to new rare disease therapeutics.

How signals shape DNA via gene regulation

A new chromatin isolation technique reveals how signaling pathways reshape DNA-bound proteins, offering insight into potential targets for precision therapies. Read more about this recent MCP paper.