JBC: Iron–sulfur cluster research offers new avenues for investigating disease

Many important proteins in the human body need iron-sulfur clusters, tiny structures made of iron and sulfur atoms, to function correctly. Researchers at the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health and the University of Kentucky have discovered that disruptions in the construction of iron-sulfur clusters can lead to the buildup of fat droplets in certain cells. These findings, published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, provide clues about the biochemical causes of such conditions as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and clear-cell renal carcinoma.

“Iron-sulfur clusters are delicate and susceptible to damage within the cell,” said , the postdoctoral fellow who led the new study. “For this reason, the cells in our body are constantly building new iron-sulfur clusters.”

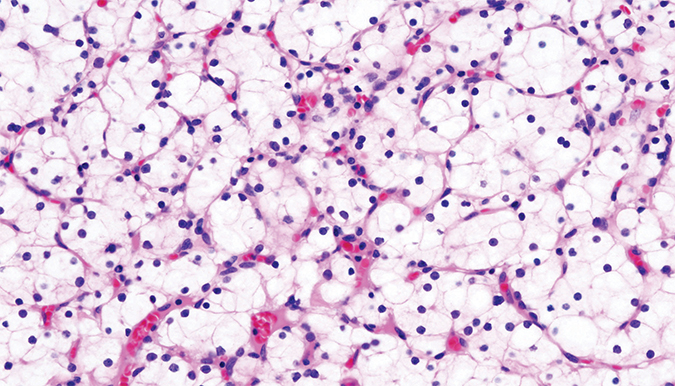

This stained histopathologic image shows clear-cell carcinoma of the kidney from a nephrectomy specimen. The cancer is named for its accumulation of lipid droplets.Courtesy of KGH/Wikimedia Commons Crooks began studying the enzymes that build iron-sulfur clusters during his graduate studies in lab at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the NIH. Mutations in one of these enzymes can cause ISCU myopathy, a hereditary condition in which patients, despite seeming strong and healthy, cannot exercise for more than a short time without feeling pain and weakness.

This stained histopathologic image shows clear-cell carcinoma of the kidney from a nephrectomy specimen. The cancer is named for its accumulation of lipid droplets.Courtesy of KGH/Wikimedia Commons Crooks began studying the enzymes that build iron-sulfur clusters during his graduate studies in lab at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the NIH. Mutations in one of these enzymes can cause ISCU myopathy, a hereditary condition in which patients, despite seeming strong and healthy, cannot exercise for more than a short time without feeling pain and weakness.

It was clear to Crooks that lifelong deficiency of iron-sulfur clusters caused profound changes in how cells processed energy. But he wondered exactly what happened in a cell in the first moments after something went wrong with iron-sulfur cluster production. Which of the many proteins that need iron-sulfur clusters were affected first, and what effect did this have on cell metabolism?

Crooks developed experimental methods to abruptly stop iron-sulfur clusters from being manufactured in cells and to monitor what happens to how these cells process glucose. Ordinarily, over a series of metabolic steps, cells would convert glucose into energy. But without iron-sulfur clusters, an enzyme called aconitase that carries out one of the steps in this process doesn’t work. As a result, the cells quickly accumulated an intermediate metabolic product called citrate, which eventually was converted into droplets of fat.

Over-accumulation of fats in tissues where they’re not normally found is a hallmark of numerous diseases, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, a risk factor for cirrhosis and liver cancer. suggest that this state could be caused by failures of iron-sulfur cluster production — for example due to cellular stressors or toxin exposure.

“We’re hoping that the people who are working so hard on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will find our paper helpful to their research,” Rouault said.

Crooks, working in the laboratory of surgeon and scientist at the NCI, is now examining the role of iron-sulfur cluster formation and aconitase function in cancers such as clear-cell carcinomas. Various cancers often are characterized by excessive fat accumulation in cells. In fact, this accumulation of lipid droplets is where clear-cell carcinomas get their name: when a slice of such a tumor is fixed on a slide and its proteins are stained, the large areas of lipid accumulation in the cells look transparent.

“We really want to look at the beginnings of cancer,” Crooks said, “… to understand whether the lipids were formed from glucose or other fuels and whether the lipids are important for pathogenesis, or whether they’re just bystanders that form in response to metabolic reprogramming, which is likely to include disruption of iron sulfur protein activities.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Elucidating how chemotherapy induces neurotoxicity

Andre Nussenzweig will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

Where do we search for the fundamental stuff of life?

Recent books by Thomas Cech and Sara Imari Walker offer two perspectives on where to look for the basic properties that define living things.

UCLA researchers engineer experimental drug for preventing heart failure after heart attacks

This new single-dose therapy blocks a protein that increases inflammation and shows promise in enhancing muscle repair in preclinical models.

The decision to eat may come down to these three neurons

The circuit that connects a hunger-signaling hormone to the jaw to stimulate chewing movements is surprisingly simple, Rockefeller University researchers have found.

Curiosity turned a dietitian into a lipid scientist

Judy Storch will receive the Avanti Award in Lipids at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

From receptor research to cancer drug development: The impact of RTKs

Joseph Schlessinger will receive the ASBMB Herbert Tabor Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)