For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

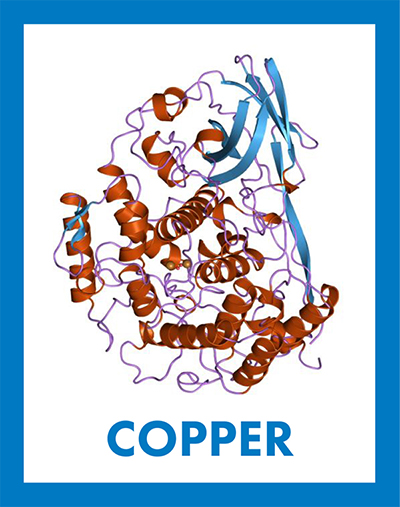

Oxygen-bound copper, represented by the two orange spheres in the center of the structure of the protein hemocyanin, gives arthropod hemolymph a blue color. Jawahar Swaminathan & MSD staff / European Bioinformatics Institute 2019 marks the 150th anniversary of the first publication of Dimitri Mendeleev’s periodic table of chemical elements. To honor the occasion, each month we are focusing on elements important in biochemistry. In January and February, we featured hydrogen and iron, respectively, and in March, we tripled down with sodium, potassium and chlorine.

For April, we have selected copper, a transition metal with chemical symbol Cu and atomic number 29. Copper participates in chemical reactions via a wide range of oxidation numbers from -2 to +4 but most commonly is found in organic cuprous and cupric complexes with oxidation states of +1 and +2, respectively.

Ancient civilizations used copper extensively in the manufacture of ornaments, weapons and tools, and the late fifth millennium BC is the archeological period known as the Copper Age.

Copper most likely forms during the of supergiant stars and makes up about 0.0068 percent of the Earth’s crust. In nature, it occurs in its pure metallic form as native copper or in combination with other elements in minerals containing copper oxides, copper sulfides or copper carbonates. These minerals form when volcanic activity separates copper from magma and the copper reacts explosively with ascending sulfurous gases, precipitating beneath the surface as .

After iron and zinc, copper is the metallic element in biological systems. Copper is indispensable for most living organisms in trace amounts, but it can produce highly reactive toxic species when found in excess inside cells. Microorganisms can mobilize solid copper by incorporating it into cyanide compounds, and copper-binding proteins in the periplasmic space allow bacteria to trap copper to avoid intracellular toxicity. In yeast, cell surface metalloreductases render copper available to high-affinity transporter proteins by reducing Cu+2 to Cu+1. Fungi that colonize the roots of host plants protect them from toxicity by trapping soiled or soluble copper in compounds with other metals.

Once in cells, copper binds to proteins that participate in electron transfer reactions or oxygen transportation. In the mitochondrial respiratory chain, a binuclear copper center in cytochrome c oxidase transfers electrons from cytochrome c to molecular oxygen in the final redox step of the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. Similarly, a copper-containing protein called plastocyanin in the thylakoid lumen of chloroplasts carries electrons between two membrane-bound proteins — cytochrome f and P700+ — during photosynthesis.

Like hemoglobin in vertebrates, a copper-containing protein called hemocyanin transports oxygen in the hemolymph of invertebrates, such as mollusks and some arthropods. When a molecule of oxygen binds two copper atoms in hemocyanin, copper is oxidized from Cu+1 to Cu+2, and the energy associated with this electron transfer changes the light-absorbing properties of copper. This causes oxygen-rich hemolymph in these animals to appear blue in contrast to the bright red color of oxygen-bound iron in hemoglobin.

In eukaryotes, the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase uses copper to catalyze the decomposition of the superoxide radical into molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, which are less toxic to the cell.

Thus, from the heart of volcanoes to the relay of electrons inside cells, copper is critical to the survival of all aerobic organisms.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.

Melissa Moore to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

A new kind of stem cell is revolutionizing regenerative medicine

Induced pluripotent stem cells are paving the way for personalized treatments to diabetes, vision loss and more. However, scientists still face hurdles such as strict regulations, scalability, cell longevity and immune rejection.

Engineering the future with synthetic biology

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on synthetic biology, featuring applications to better human and environmental health.

Scientists find bacterial ‘Achilles’ heel’ to combat antibiotic resistance

Alejandro Vila, an ASBMB Breakthroughs speaker, discussed his work on metallo-β-lactamase enzymes and their dependence on zinc.

Host vs. pathogen and the molecular arms race

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on host–pathogen interactions, to be held Sunday, April 13 at 1:50 p.m.