JLR: Secrets of fat and the lymph node

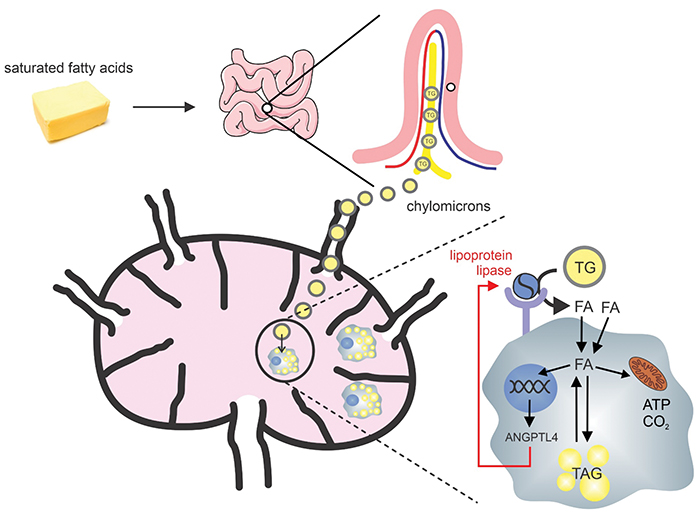

When you eat a high-fat meal, your gut exports the fat into chylomicrons, which join the flow of lymph in the surrounding vessels. This combined fluid, which resembles cream, passes rapidly through the lymph nodes and into the blood stream, where the fat is absorbed by cells that need energy, like heart muscle cells, or that can store fat for the long term, like adipose tissue.

, a professor and department chair at Wageningen University in the Netherlands, studies that rapid uptake system, which depends on a protein called lipoprotein lipase, or LPL for short. LPL breaks down triglyceride fat molecules, allowing them to be absorbed. Kersten’s in the Journal of Lipid Research shows that LPL regulation varies among tissues.

Too much fat in the blood can cause problems such as heart disease. Therefore, right after a meal, it is beneficial for adipose tissue to absorb fat rapidly for storage. That means bumping up LPL levels. But during a long fast, limited LPL activity in adipose tissue helps ensure that fat stays available to cells that need it for energy. It is important that our bodies can tune LPL activity in different systems in response to how much food we eat.

Some 20 years ago, as a postdoc, Kersten isolated a protein, ANGPTL4, that acts as a control dial for LPL. Later, his lab demonstrated that the protein targets LPL for degradation in adipose cells. Researchers since have found that ANGPTL4 fluctuates in response to fasting, cold exposure and exercise, helping to control the body’s lipid use.

A cartoon Kersten uses for teaching shows how saturated fat from the diet enters the lymph node as chylomicrons and how lymph node resident macrophages respond to the fat.Courtesy of Sander KerstenDrug developers hoped that reducing ANGPTL4 would be a good way to reduce the risk of heart disease, but this research hit a snag. Mice that were bred to have no ANGPTL4 appeared healthy at first, but that health was fragile.

A cartoon Kersten uses for teaching shows how saturated fat from the diet enters the lymph node as chylomicrons and how lymph node resident macrophages respond to the fat.Courtesy of Sander KerstenDrug developers hoped that reducing ANGPTL4 would be a good way to reduce the risk of heart disease, but this research hit a snag. Mice that were bred to have no ANGPTL4 appeared healthy at first, but that health was fragile.

“If you place these animals on a diet that’s rich in fat, they develop complications which were unanticipated,” Kersten said. Lymph carrying chylomicrons escapes into their abdomens, eventually killing the mice. Whether this would happen in humans if you blocked their ANGPTL4 isn’t known — it’s an experiment no one is willing to risk.

The Kersten lab’s latest paper examines why loss of ANGPTL4 has this effect. The work focuses on macrophages, the cells that populate the lymph node. Like fat cells, macrophages express ANGPTL4, and like fat cells, they turn it up in response to high fat in the bloodstream. But ANGPTL4 in macrophages appears to work differently than in fat cells. Although ANGPTL4 reduces LPL activity and fat uptake in macrophages, it doesn’t seem to alter LPL level — suggesting that it does not act by targeting LPL for degradation but by another mechanism. Exactly how ANGPTL4 affects macrophages, Kersten said, remains to be determined.

“After 20 years of studying ANGPTL4, there are some things that are very, very clear about this protein,” Kersten said. “And I’m happy to have contributed to that.”

Other questions remain. “We’re not still 100% sure about what is going on in the lymph nodes.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Elucidating how chemotherapy induces neurotoxicity

Andre Nussenzweig will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

Where do we search for the fundamental stuff of life?

Recent books by Thomas Cech and Sara Imari Walker offer two perspectives on where to look for the basic properties that define living things.

UCLA researchers engineer experimental drug for preventing heart failure after heart attacks

This new single-dose therapy blocks a protein that increases inflammation and shows promise in enhancing muscle repair in preclinical models.

The decision to eat may come down to these three neurons

The circuit that connects a hunger-signaling hormone to the jaw to stimulate chewing movements is surprisingly simple, Rockefeller University researchers have found.

Curiosity turned a dietitian into a lipid scientist

Judy Storch will receive the Avanti Award in Lipids at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.

From receptor research to cancer drug development: The impact of RTKs

Joseph Schlessinger will receive the ASBMB Herbert Tabor Research Award at the 2025 ASBMB Annual meeting, April 12–15 in Chicago.